After reading Stefanie's post on Proust I thought that I'd post the famous Proust Questionaire.

Here are Proust's answers at 7:

What do you regard as the lowest depth of misery? To be separated from Mama

Where would you like to live? In the country of the Ideal, or, rather, of my ideal

What is your idea of earthly happiness? To live in contact with those I love, with the beauties of nature, with a quantity of books and music, and to have, within easy distance, a French theater

To what faults do you feel most indulgent? To a life deprived of the works of genius

Who are your favorite heroes of fiction? Those of romance and poetry, those who are the expression of an ideal rather than an imitation of the real

Who are your favorite characters in history? A mixture of Socrates, Pericles, Mahomet, Pliny the Younger and Augustin Thierry

Who are your favorite heroines in real life? A woman of genius leading an ordinary life

Who are your favorite heroines of fiction? Those who are more than women without ceasing to be womanly; everything that is tender, poetic, pure and in every way beautiful

Your favorite painter? Meissonier

Your favorite musician? Mozart

The quality you most admire in a man? Intelligence, moral sense

The quality you most admire in a woman? Gentleness, naturalness, intelligence

Your favorite virtue? All virtues that are not limited to a sect: the universal virtues

Your favorite occupation? Reading, dreaming, and writing verse

Who would you have liked to be? Since the question does not arise, I prefer not to answer it. All the same, I should very much have liked to be Pliny the Younger.

Seven years later, age 20:

Your most marked characteristic? A craving to be loved, or, to be more precise, to be caressed and spoiled rather than to be admired

The quality you most like in a man? Feminine charm

The quality you most like in a woman? A man's virtues, and frankness in friendship

What do you most value in your friends? Tenderness - provided they possess a physical charm which makes their tenderness worth having

What is your principle defect? Lack of understanding; weakness of will

What is your favorite occupation? Loving

What is your dream of happiness? Not, I fear, a very elevated one. I really haven't the courage to say what it is, and if I did I should probably destroy it by the mere fact of putting it into words.

What to your mind would be the greatest of misfortunes? Never to have known my mother or my grandmother

What would you like to be? Myself - as those whom I admire would like me to be

In what country would you like to live? One where certain things that I want would be realized - _and where feelings of tenderness would always be reciprocated_. [Proust's underlining]

What is your favorite color? Beauty lies not in colors but in thier harmony

What is your favorite flower? Hers - but apart from that, all

What is your favorite bird? The swallow

Who are your favorite prose writers? At the moment, Anatole France and Pierre Loti

Who are your favoite poets? Baudelaire and Alfred de Vigny

Who is your favorite hero of fiction? Hamlet

Who are your favorite heroines of fiction? Phedre (crossed out) Berenice

Who are your favorite composers? Beethoven, Wagner, Shuhmann

Who are your favorite painters? Leonardo da Vinci, Rembrandt

Who are your heroes in real life? Monsieur Darlu, Monsieur Boutroux (professors)

Who are your favorite heroines of history? Cleopatra

What are your favorite names? I only have one at a time

What is it you most dislike? My own worst qualities

What historical figures do you most despise? I am not sufficiently educated to say

What event in military history do you most admire? My own enlistment as a volunteer!

What reform do you most admire? (no response)

What natural gift would you most like to possess? Will power and irresistible charm

How would you like to die? A better man than I am, and much beloved

What is your present state of mind? Annoyance at having to think about myself in order to answer these questions

To what faults do you feel most indulgent? Those that I understand

What is your motto? I prefer not to say, for fear it might bring me bad luck.

Yes, 7 and 20. It almost doesn't seem real, that someone, let alone at such young and impressionable ages, could answer these questions with such perfection.

I'd post my responses, but then people may see me for who I really am and that may be better left unseen.

Friday, June 23, 2006

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

When we set out to do something, does it ever happen as we expected? Going to the grocery store, do we only stick the listed items? Ok, that's maybe a bad analogy for the voyage of the pilgrims on the Mayflower, but I'm trying here. Imagine setting out for a new world, still vastly undiscovered and certainly unreliable.

When he later wrote about the voyage of the Mayflower, Bradford devoted only a few paragraphs to describing a passage that lasted more than two months. The physical and psychological punishment endured by the passengers in the dark and dripping 'tween decks was compounded by the terrifying lack of information they possessed concerning their ultimate destination. All they knew for certain was that if they did somehow succeed in crossing this three-thousand-mile stretch of ocean, no one-except perhaps for some hostile Indians-would be there to greet them.

I may not have agreed with their religion, but those on the Mayflower had conviction like I've never known. Their voyage to America was supposed to be the great beginning of a life of religious freedom. Basically kicked out of England at the beginning of the 17th Century for their reformist views on the Church, the English Separatists found refuge in Leiden, Holland. After nearly 12 years in Holland, they were beginning to wear out their welcome. Next stop America.

Young William Bradford was one of the first men of the congregation to sign up for the voyage. However, Bradford and his wife Dorothy, decided to leave their son John in Holland, presumably with her family. It would have been a dangerous passage and then the settlement would be another terrible ordeal. I don't know if William and Dorothy were right in leaving their son behind, but I want to find out.

Now reading:

Nathaniel Philbrick Mayflower

Jeanette Winters Lighthousekeeping

When he later wrote about the voyage of the Mayflower, Bradford devoted only a few paragraphs to describing a passage that lasted more than two months. The physical and psychological punishment endured by the passengers in the dark and dripping 'tween decks was compounded by the terrifying lack of information they possessed concerning their ultimate destination. All they knew for certain was that if they did somehow succeed in crossing this three-thousand-mile stretch of ocean, no one-except perhaps for some hostile Indians-would be there to greet them.

I may not have agreed with their religion, but those on the Mayflower had conviction like I've never known. Their voyage to America was supposed to be the great beginning of a life of religious freedom. Basically kicked out of England at the beginning of the 17th Century for their reformist views on the Church, the English Separatists found refuge in Leiden, Holland. After nearly 12 years in Holland, they were beginning to wear out their welcome. Next stop America.

Young William Bradford was one of the first men of the congregation to sign up for the voyage. However, Bradford and his wife Dorothy, decided to leave their son John in Holland, presumably with her family. It would have been a dangerous passage and then the settlement would be another terrible ordeal. I don't know if William and Dorothy were right in leaving their son behind, but I want to find out.

Now reading:

Nathaniel Philbrick Mayflower

Jeanette Winters Lighthousekeeping

Tuesday, June 20, 2006

My head's been all over the place recently. That's my excuse for lack of posts. I'm still reading Atwood's The Blind Assassin and I'm getting deep into it. But I also bought Nathaniel Philbrick's Mayflower. I wanted to read a work of non-fiction, so I got this hardcover...at Costco. Hey, I'm an advocate of independent bookstores, but it's a brand new hardcover and it was only $16. I couldn't pass it up. Ok, I could have, but I didn't. I lack will power. Always have. So that's two books I'm reading and I don't know how to write about non-fiction, but I'll give it a go tomorrow.

It was supposed to be in the low 80s today in Boston with chance of rain. Yesterday was 90 and Sunday it was about 98 or 114 degrees. Today, at 81 or 82, I thought it would feel like a reprieve. It didn't. Anyway, I went to my courtyard to read, but only lasted about 15 minutes there before scampering inside, making straight away for the cooler aisles of the library. Three books and 30 minutes later, I was on my way back outside and off to the dreaded cubicle life. At least Kenneth Harvey's The Town That Forgot How to Breathe, Marina Lewycka's A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainian and Jeanette Winterson's Lighthousekeeping were tucked, and stuck, under my arm, set to keep me company in my cube. If misery loves company, boredom and heat love books.

It was supposed to be in the low 80s today in Boston with chance of rain. Yesterday was 90 and Sunday it was about 98 or 114 degrees. Today, at 81 or 82, I thought it would feel like a reprieve. It didn't. Anyway, I went to my courtyard to read, but only lasted about 15 minutes there before scampering inside, making straight away for the cooler aisles of the library. Three books and 30 minutes later, I was on my way back outside and off to the dreaded cubicle life. At least Kenneth Harvey's The Town That Forgot How to Breathe, Marina Lewycka's A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainian and Jeanette Winterson's Lighthousekeeping were tucked, and stuck, under my arm, set to keep me company in my cube. If misery loves company, boredom and heat love books.

Monday, June 19, 2006

She stubs out her cigarette in the brown glass ashtray, then settles herself against him, ear to his chest. She likes to hear his voice this way, as if it begins not in his throat but in his body, like a hum or a growl, or like a voice speaking from deep underground. Like the blood moving through her own heart: a word, a word, a word.

- Margaret Atwood The Blind Assassin

- Margaret Atwood The Blind Assassin

Friday, June 16, 2006

Twenty-five years ago Bukowski was a literary outcast. Now the author of Notes of a Dirty Old Man will be housed at the Huntington Library in California. My, how far we've come.

Thursday, June 15, 2006

When I finally got home with my new purchases around 8 p.m., I had The Blind Assassin on my mind, but the soccer field was calling me. New soccerball? Check. New cleats? Check. I played until just around 9 p.m., when the light faded enough that I would have injured myself in one of the all too common potholes that potmark the field.

I feel like I cheated on Atwood. I didn't mean to, but even a former athlete and current oaf like me has to do get off the couch every now and again.

And getting on the field again, even if by myself and only for a little while, I know why people write books and movies about sport. Smelling the grass, the feel of my boots squishing in the not firm ground, made me think of The Natural. I guess that's only because there are no great soccer movies to relate to.

Just thought I'd share that tonight. I felt young again...if only for a night.

Reading now:

Margaret Atwood The Blind Assassin

Listening to:

Frank Sinatra In the Wee Small Hours

I feel like I cheated on Atwood. I didn't mean to, but even a former athlete and current oaf like me has to do get off the couch every now and again.

And getting on the field again, even if by myself and only for a little while, I know why people write books and movies about sport. Smelling the grass, the feel of my boots squishing in the not firm ground, made me think of The Natural. I guess that's only because there are no great soccer movies to relate to.

Just thought I'd share that tonight. I felt young again...if only for a night.

Reading now:

Margaret Atwood The Blind Assassin

Listening to:

Frank Sinatra In the Wee Small Hours

Things no one told me. 1)Margaret Atwood is great. 2)Margaret Atwood is a post-modernist. 3)Margaret Atwood gives David Mitchell a run for his money. All of the above were unbeknownst to be me...until now.

Atwood's The Blind Assassin tells the story, I think, of Iris Chase Griffen. But it's Iris's sister Laura Chase that retains most of my attention. Or at least, begs my attention.

Ten days after the war ended, my sister Laura drove a car off a bridge.

Come on. She can't really start a novel with a sentence like that, can she? It's brilliant. Through the first 140 pages or so, Iris is telling us her life story in a way. Iris is now 80 years old and living on her own. She tells the story of her family's button factory and their strange tale of war, courtship, shell-shock, death and buttons. But intricately placed within this relatively common storytelling concept, Atwood has placed chapters of Laura's posthumously published novel, The Blind Assassin, as section breaks. Laura's Assassin narrative is about two unnamed lovers secretly meeting in rundown places to make love and tell stories. The unnamed man is telling the woman a story that I figure takes place in the future, or something of the sort. It's a bizarre story, but hell, it's enticing.

The more of Atwood I read, the more I look back on Mitchell's Cloud Atlas as an almost tame book. His sections were separate narratives stitched together with a sometimes obvious connection. Atwood doesn't explain herself like Mitchell does. She doesn't tie things up. At least not yet.

Atwood's The Blind Assassin tells the story, I think, of Iris Chase Griffen. But it's Iris's sister Laura Chase that retains most of my attention. Or at least, begs my attention.

Ten days after the war ended, my sister Laura drove a car off a bridge.

Come on. She can't really start a novel with a sentence like that, can she? It's brilliant. Through the first 140 pages or so, Iris is telling us her life story in a way. Iris is now 80 years old and living on her own. She tells the story of her family's button factory and their strange tale of war, courtship, shell-shock, death and buttons. But intricately placed within this relatively common storytelling concept, Atwood has placed chapters of Laura's posthumously published novel, The Blind Assassin, as section breaks. Laura's Assassin narrative is about two unnamed lovers secretly meeting in rundown places to make love and tell stories. The unnamed man is telling the woman a story that I figure takes place in the future, or something of the sort. It's a bizarre story, but hell, it's enticing.

The more of Atwood I read, the more I look back on Mitchell's Cloud Atlas as an almost tame book. His sections were separate narratives stitched together with a sometimes obvious connection. Atwood doesn't explain herself like Mitchell does. She doesn't tie things up. At least not yet.

Tuesday, June 13, 2006

In the kitchen, there's one window that opens up onto the backyard and looks toward the beach. The kitchen gets the cross breeze, the living room gets traffic noise. Somehow this doesn't seem right. I spend more time in the living room and instead of gentle, salt scented air wafting through the room, I get cars thumping music, horns and ambulances. Not a situation conducive to reading...or blogging, but I try.

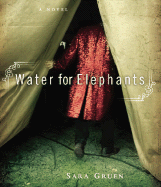

I finished Sara Gruen's Water for Elephants in this very room, two flights above screeching brakes and and trembling bass. I had never read Gruen before, but knew that she had an affinity for animals in her writing. Water for Elephants is no different. It tells the story of Jacob, a veteranarian school dropout from Cornell who catches on with a traveling circus during The Depression. He becomes the defacto vet and becomes a member of the bizarre. What's unusual about this novel, at least what I found unusual, is that the freaks, geeks, fat ladies and clowns are secondary characters. Instead, Gruen focuses on the roustabouts and the animal handlers. Basically, we're given enough time to see otherside of the circus, where cruelty and good faith are often times blurred. Why? Because the world is like that.

Jacob of course falls in love with the beautiful Marlena who performs with the horses and the elephant Rosie. But it's Marlena's belligerent husband August that stands between the two lovers. Though the love affair is an obvious eventuality, Gruen handles the circus jargon and doesn't get tied up trying to explain it all too much. As Jacob learns the life of the circus, so do we.

Just finished:

Sara Gruen Water for Elephants

Now reading:

Margaret Atwood The Blind Assassin

Listening to:

The street

Monday, June 12, 2006

The sun stopped lighting this part of the earth hours ago. With the black and blue night now fully encompassing the houses, trees and cars along my street, I somehow get lost in my thoughts again. I think more at night. Not better. More.

I haven't considered myself a writer for sometime now. I'm a reader and I know that. But Julian Barnes wonders who we read for. If critics have already written eloquently and insightful essays on a particular book and we have nothing new or better to add, then why do we read the book? Why? Because by reading it, it becomes yours. I'm interested in this idea that we, as readers, become possessive of a book, that we take it and make it our own. However, Barnes carries the analogy one step further...how we possess our lives.

But life, in this respect, is a bit like reading. And as I said before: if all your responses to a book have already been duplicated and expanded upon by a professional critic, then what point is there to your reading? Only that it becomes yours. Similarly, why live your life? Because it's yours. But what if such an answer gradually becomes less and less convincing?

Barnes's narrator, George Braithwaite, is writing about his wife's attempted suicide, but I think the idea, or rather, the question is much larger than that. Is Barnes challenging us to make our lives more convincing, to make our lives worthwhile? Possibly, because like great art, I become encouraged and motivated after experiencing it...and like great art, the subject is open to interpretation. That is what I'm leaving with tonight. My life, though ordinary to the highest degree, has not been duplicated and only I can expand upon on it. I am my own critic and I am taking back my life...with the little help of a book.

I'm still here. Crazy weekend, but tonight I'll be ready to write a bit about the rest of Flaubert's Parrot and the first 100 pages of Sara Gruen's Water for Elephants.

Just finished:

Julian Barnes Flaubert's Parrot

Now reading:

Sara Gruen Water for Elephants

Just finished:

Julian Barnes Flaubert's Parrot

Now reading:

Sara Gruen Water for Elephants

Wednesday, June 07, 2006

Parrots only learn and repeat words, sayings, phrases, sounds, that they've been taught or have heard over a long period of time. There's one at my dog's vet that sounds like a Nextel phone. It's uncanny. Is Flaubert's fascination with the parrot metaphorical for the life of a writer? Do writers only regurgitate what they've heard before? Or is there actual creation in the writing, true art? And now that I think about it, what makes me believe that Flaubert was fascinated by the parrot? Is it because Barnes writes that Flaubert possibly had two stuffed parrots (but at different locations) and stared at them while writing Un coeur simple, A Simple Heart? Within three weeks, the parrot began to "irritate him," Barnes states.

Flaubert may have been of the literary philosophy, some call him the first Modern writer, that there is no deeper meaning in novels. They are what they are. But Barnes seems to revel in this idea of Flaubert who, with every novel, wrote more and more about his life, even if subconsciously.

We can, if we wish (and if we disobey Flaubert), submit the bird to additional interpretation. For instance, there are submerged parallels between the life of the prematurely aged novelist and the maturely aged Felicite. Critics have sent in the ferrets. Both of them were solitary; both of them had lives stained with loss; both of them, though full of grief, were persevering. Those keen to push things further suggest that the incident in which Felicite is struck down by a mail-couch on the road to Honfleur is a submerged reference to Gustave's first epileptic fit, when he was struck down on the road outside Bourg-Achard. I don't know. How submerged does a reference have to be before it drowns?

I don't know either Julian, but I'm going to read the rest of your book to see if I can get a better glimpse. So far, I don't know if Flaubert's Parrot is more of a testament to Flaubert's or Barnes's brilliance and I don't know if I ever will.

Flaubert may have been of the literary philosophy, some call him the first Modern writer, that there is no deeper meaning in novels. They are what they are. But Barnes seems to revel in this idea of Flaubert who, with every novel, wrote more and more about his life, even if subconsciously.

We can, if we wish (and if we disobey Flaubert), submit the bird to additional interpretation. For instance, there are submerged parallels between the life of the prematurely aged novelist and the maturely aged Felicite. Critics have sent in the ferrets. Both of them were solitary; both of them had lives stained with loss; both of them, though full of grief, were persevering. Those keen to push things further suggest that the incident in which Felicite is struck down by a mail-couch on the road to Honfleur is a submerged reference to Gustave's first epileptic fit, when he was struck down on the road outside Bourg-Achard. I don't know. How submerged does a reference have to be before it drowns?

I don't know either Julian, but I'm going to read the rest of your book to see if I can get a better glimpse. So far, I don't know if Flaubert's Parrot is more of a testament to Flaubert's or Barnes's brilliance and I don't know if I ever will.

I'd ban coincidences, if I were a dictator of fiction. Well, perhaps not entirely. Coincidences would be permitted in the picaresque; that's where they belong. Go on, take them: Let the pilot whose parachute has failed to open land in a haystack, let the virtuous pauper with the gangrenous foot discover the buried treasure-it's all right, it doesn't really matter.

One way of legitimising coincidences, of course, is to call them ironies. That's what smart people do. Irony is, after all, the modern mode, a drinking companion for resonance and wit. Who could be against it? And yet, sometimes I wonder if the wittiest, most resonant isn't just a well-brushed, well-educated coincidence.

- Julian Barnes Flaubert's Parrot

I'm enamored with Barnes's intellectual game he calls a novel.

I just got in to work, wet and soggy from the New England rain, and just wanted to write this up quick. I couldn't stop thinking about Barnes playing with the concept of literature. This quote is a microcosm of the book so far. At first you think he's going to be serious about coincidences, but by the end, I don't know if he's still anti-coincidence or what. Maybe that's the point? I love the book so far anyway. It's a like a brainteaser.

When I get home tonight, I'm going to attempt to write about my perception of the parrot as writer metaphor that Barnes and Flaubert tackle. If they could do it, I should have no problem. Piece of cake.

One way of legitimising coincidences, of course, is to call them ironies. That's what smart people do. Irony is, after all, the modern mode, a drinking companion for resonance and wit. Who could be against it? And yet, sometimes I wonder if the wittiest, most resonant isn't just a well-brushed, well-educated coincidence.

- Julian Barnes Flaubert's Parrot

I'm enamored with Barnes's intellectual game he calls a novel.

I just got in to work, wet and soggy from the New England rain, and just wanted to write this up quick. I couldn't stop thinking about Barnes playing with the concept of literature. This quote is a microcosm of the book so far. At first you think he's going to be serious about coincidences, but by the end, I don't know if he's still anti-coincidence or what. Maybe that's the point? I love the book so far anyway. It's a like a brainteaser.

When I get home tonight, I'm going to attempt to write about my perception of the parrot as writer metaphor that Barnes and Flaubert tackle. If they could do it, I should have no problem. Piece of cake.

Monday, June 05, 2006

I don't know what it is about The Name of the Rose, but it's not the same Eco from The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana. His writing is fluid, precise and difficult, but it's making for a fairly tedious book. I don't read with a dictionary at hand and I seldom, if ever, refer to a dictionary when I'm done with a book. If I don't know what the word means, then I don't want to know or I like to think the author didn't want us to know, therefore it's not integral to the novel. Eco surely doesn't expect his readers to know all the Latin he uses in Name of the Rose and I couldn't imagine looking up the words. Instead, it's all a matter of the words flowing and speaking of the novel in the scientific, ancient way in which they're spoken by the monks. I like that. But Eco has taken it too far. It's a long novel and it's being dragged down with the Latin terms and sayings. And I know it's much more than a mystery, but there seems to be too much going on. I feel like young Adso following brilliant William, but not necessarily knowing what he's speaking about. Not a fun way to spend your spare time.

I'm halfway through and should finish it this week, but Eco is not making me want to finish it and that I have a problem with. Saramago, who I somehow keep comparing Eco to, never tries to make his readers feel inferior. Eco, is coming off as being smarter-than-thou. And if I was smarter now, I'd drop the book for a more enjoyable read, but a quitter I'm not. At least not yet.

Eco said it perfectly himself: Graecum est, non legitur

It is Greek to me

I'm halfway through and should finish it this week, but Eco is not making me want to finish it and that I have a problem with. Saramago, who I somehow keep comparing Eco to, never tries to make his readers feel inferior. Eco, is coming off as being smarter-than-thou. And if I was smarter now, I'd drop the book for a more enjoyable read, but a quitter I'm not. At least not yet.

Eco said it perfectly himself: Graecum est, non legitur

It is Greek to me

Thursday, June 01, 2006

I stole my friend's respite spot. I know, I'm awful. The Boston Public Library, though some parts are beautiful and gothic, most of the library is similar to the cement based buildings of the 1970s. Danielle at A Work in Progress wrote about Brutalism architecture in a recent post. That is the BPL. But in between the divergent library wings is a courtyard, complete with gurgling fountain, flowers, plants and green. Now it's mine. Lunch hours are eased away in a seat by the fountain, book harmlessly held shut, eyes hesitantly closed and the city and work far away. After work, for a cool down, I sit and try not to worry about the next day. Do I read there? Hardly. I dream there. It is mine.

She claims she can no longer go there because I've stolen it. Why she can't continue to go there is beyond me, but I don't mind, I'll take it. For her it's a park bench on Comm Ave. among walkers, workers and wanderers passing as she tries to steal a few pages. I may also have workers and wanderers, but we are a chosen few who have selected this hideaway as our escape and relinquish it, we won't. You can find me there tomorrow too. And the day after.

She claims she can no longer go there because I've stolen it. Why she can't continue to go there is beyond me, but I don't mind, I'll take it. For her it's a park bench on Comm Ave. among walkers, workers and wanderers passing as she tries to steal a few pages. I may also have workers and wanderers, but we are a chosen few who have selected this hideaway as our escape and relinquish it, we won't. You can find me there tomorrow too. And the day after.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)